Thanks again to the more than 250 of you who completed our reader survey a couple of weeks ago. We reported the basic demographics of readers in a post last week, and promised you some more detailed analysis this week – particularly of the two questions where we gave people the option of adding their own thoughts as free text.

Thanks again to the more than 250 of you who completed our reader survey a couple of weeks ago. We reported the basic demographics of readers in a post last week, and promised you some more detailed analysis this week – particularly of the two questions where we gave people the option of adding their own thoughts as free text.

There’s no way we can present every nugget of interesting information emerging from the survey, but we thought it was worth digging into a few of the more obvious or unexpected features of the data. Firstly, a little additional analysis of the more quantitative data emerging from the survey.

Who are our readers?

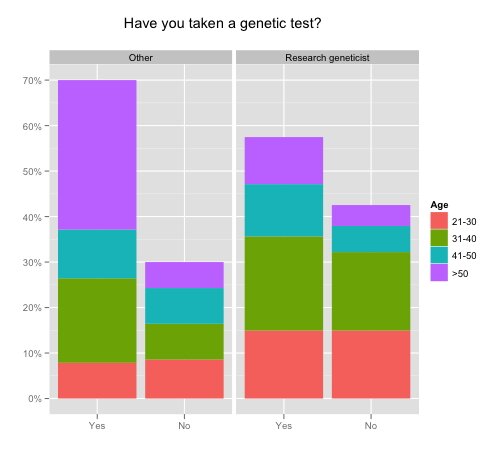

One interesting feature of our readers that emerged from the survey data was that you are (very broadly) composed of two groups. One group consists of experts in genetics and genomics, many of whom work in genetic research, the biotech industry, or other fields related to DNA, and who tend on average to be young (in other words, the classic profile of a genetics blog reader). The second group is much more diverse, but contains individuals who tend to be older, report a lower level of background knowledge about genetics, and are more likely to work in fields unrelated to genetics. What does the second group have in common? Most of them have taken a direct-to-consumer genetic test. You can see the differences in respondent characteristics in the graph below:

So it appears we have one group of readers who follow Unzipped because they know a lot about genetics, but who may or may not have actually had a genetic test themselves; and a second group who follow us because they have had a genetic test, but who may or may not have a strong background in genetics. This is in hindsight unsurprising and quite reassuring, since these two groups (experts and genetic test-takers) are exactly who we have been hoping to communicate with and create dialogue between. However, the survey has reminded us that we need to do a better job of creating interest among other groups: in particular, we would love to get better representation from clinicians (and especially genetic counsellors).

The presence of these two distinct groups among our readers created a fascinating ascertainment bias that had strange effects on our survey data: for instance, contrary to expectations and data from larger surveys of DTC testing customers, we found that genetic test-takers in our sample tended to be less educated and have less background knowledge in genetics than non-testers. This effect arises simply because while we probably draw our readers more-or-less randomly from the population of genetic test-takers, the people who read Genomes Unzipped without having taken a genetic test are motivated to read us for other reasons (such as a professional interest in genetics, or general interest in science blogs) and thus have heavily skewed demographics.

Breaking down responses to ethical questions

We asked readers a number of questions about their attitudes towards controversial topics in genomics, such as public genetic data sharing and whether parents should be able to consent minors for genetic testing.

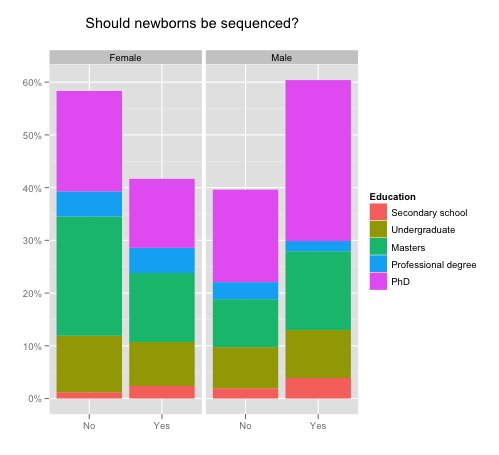

One controversial question was whether newborns should routinely have their whole genomes sequenced, once the technology becomes affordable. Here the results appeared to be heavily affected by the sex of the respondent: males were far more likely (60.4%) to respond positively to this question than females (41.2%), a difference that was statistically significant (P < 0.01):

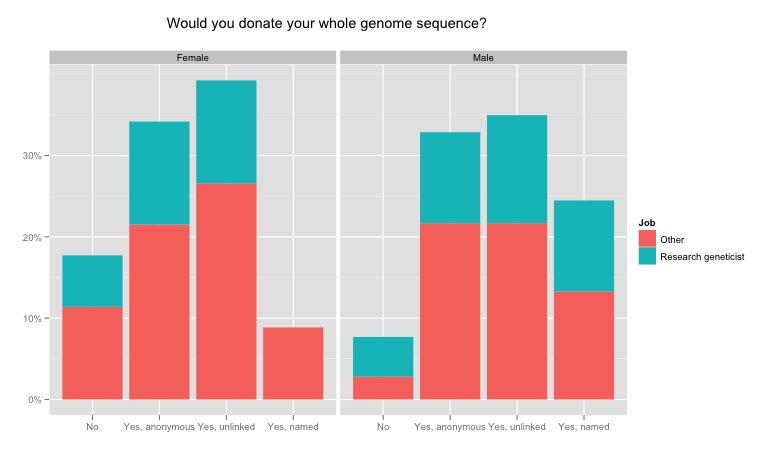

We also asked whether people would be interested in donating their own genetic data to a project like Genomes Unzipped, under various conditions: under no circumstances; only if anonymity could be guaranteed; with no guarantee of anonymity, so long as data weren’t publicly linked to the individual’s name; and finally, completely open sharing in which the information was linked to the individual’s identity.

Here the male-female divide was also quite stark:

Males were far more likely than females to agree to donate their data completely openly, whereas females were more likely than males to indicate that they wouldn’t donate their data under any circumstances (again, statistically significant at P < 0.01). Remarkably, there were precisely zero female research geneticists who were willing to make their sequence data completely openly available. Feel free to indulge in idle speculation about the evolutionary psychology underlying this trend in the comments…

What direct harms have been experienced by DTC genetic test customers?

We asked participants if they had experienced direct harm from a direct-to-consumer genetic test or knew of someone else who had, and 10 people (4%) replied that they had, a surprisingly high number.

However, on closer inspection of the details provided by these 10 individuals, we found that four responses didn’t really fit any reasonable criteria for harm:

- one respondent provided no details;

- one response was uninterpretable (“I”ve been in a media war for a year or so.”);

- two separate respondents know customers disappointed by unexpected or boring ancestry results.

There were also four responses indicating that the respondent knew of someone else who had a negative experience with DTC testing:

- the respondent knew someone affected by 23andMe sample mix-up, noting that if there hadn’t been obviously incorrect ancestry information the customer might have acted on at least one risk report;

- the respondent knew a customer unduly concerned about reported diabetes risk from a DTC test;

- the respondent reported counselling “several” patients with strong family histories of colorectal cancer who were falsely reassured by Navigenics reports of reduced colon cancer risk – respondent said “[n]ot so much harm as a lot of confusion and frustration on the part of the patients (“what did I pay for?” type of reaction)“;

- the respondent reported counselling two individuals who tested positive for BRCA and APOE risk variants and interpretation from DTC providers (23andMe and Navigenics, respectively) that was “not meeting the person’s needs”. Here the respondent further noted: “The “harm” here was not physical, but insufficient training of the interpretation/counseling staff (and would likley have been just as likely to occur in a primary care medical practice or even most medical practice other than at places with a network of genomic experts–so it’s not DTC genomics but a general problem of expertise and relative paucity of experts, and a health professional intermediary is not necessarily an improvement.“

So one reported case of potential (but not actual) harm; one reported case of unjustified concern about disease risk as a result of a DTC test; and several reported cases of confusion emerging from test results that later needed to be corrected by a medical professional.

Finally, there were two cases where the respondent themselves reported a negative experience with DTC testing:

- one respondent argued that the interpretation of their own CYP2D6 null allele homozygosity by Pathway Genomics was seriously inadequate, referring to tenuous association with Tamoxifen metabolism and not reporting better-established links to well-established, serious drug metabolism problems;

- a second respondent ordered a DTC genetic test from a Canadian company, BioResolve, paid ~US$400-500, but has never received results and the company no longer responds to email queries. [The company has been the subject of numerous customer complaints, and their website seems more-or-less defunct].

So of the 166 respondents who reported having taken at least one genetic test, only one reported a negative experience (the second individual’s negative experience was as a result of not being able to take a genetic test). This negative experience relates to perceived inadequacy of interpretation, and it seems that no actual direct harm was done here.

Acknowledging once again the ascertainment bias in our sample (which is likely skewed towards people with an overall positive view of genetic testing), these results suggest that while testing companies could do better in providing interpretation when returning results related to serious diseases, there’s no evidence here of serious harm being done as a result of DTC testing. That’s a reassuring outcome.

What misconceptions about genetics are readers most concerned about?

We included a free-text box at the very end of the survey asking a question suggested by Mary Carmichael: What public misconceptions about genetics are most concerning to you? How do you think these misconceptions can/should be corrected?

We received (by my count) 121 on-topic responses to this question, many of them lengthy and extremely interesting. There’s no way I can do justice to the variety and thoughtfulness of the replies in a single blog post (and I also completely lack the background in qualitative research required to mine the data effectively), so instead I have edited the responses to strip out identifying information and off-topic answers (my apologies to the half-dozen people who used this box to complain about the overly restrictive responses to some survey questions!), cleaned up some formatting, and made the entire data-set publicly available as a Google document. I hope that this list of concerns about public misconceptions from a set of highly educated, genetics-savvy individuals will be useful for other bloggers or writers interested in correcting these concerns.

[Added in edit: in the comments below, Dan Vorhaus adds his analysis of the responses to this question.]

If anyone with a background in qualitative research wants to have a go at crunching the responses they would be more than welcome, but I can tell you that there were a few clear trends. The single biggest misconception cited (unsurprisingly) was genetic determinism, the notion that genes are solely responsible for all human ills. Related concerns were the simplistic “one gene –> one disease” model sometimes perpetuated by lazy journalists, and the possibility that genetic test customers will view their results as more predictive of disease risk than they actually are. Genetic exceptionalism (the notion that genetic risk factors are somehow different from other classes of risk) was also a common theme.

When it came to suggesting how these misconceptions could be corrected, a few themes emerged: we need better education of the public (and clinicians) about genetics and risk, more nuanced stories in the mainstream media, better engagement between genetic researchers and the public, and a purging of charlatans from the DTC genetics industry. Many respondents argued that the public would be able to grasp complex genetics concepts if given the opportunity; others were more fatalistic, pondering whether the public will ever be anything more than ignorant about genetics.

In closing, I wanted to highlight two of the many thoughtful comments regarding how public misconceptions about genetics could be corrected. Firstly:

Two thoughts regarding how misconceptions could be corrected: firstly, we need to capture the heart and not just the mind of the public. Genetics says things about humanity and personal identity and we need influential non-scientists to immerse themselves in the revolution and be inspired by its promise, beauty and uncertainties.

Secondly we need consumer support. The power of consumers is one of the strongest undercurrents of modern culture, it brought GM crops to its knees but could be the key to fulfilling the potential of human genetic testing.

And a suggestion for dealing with genetic determinism:

To correct this misconception, data from an intervention study can show how subject “overcame” their genome sequence (i.e., really a small number of alleles) to now have healthier clinical measures of disease status (e.g., lower BMI or lower blood lipids). To correct this, a whole load of healthy and reproductive people with “bad genes” can be presented to the public – look, it’s not just this or that bad gene, but is a complex interplay between many, many variants and the environment.

RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter

By the way, special thanks to Kate for the pretty pictures in the post, and Luke for doing a fancy-schmancy PCA that unfortunately didn’t tell us what we wanted it to and thus didn’t make it into the post…

Mmm, science.

If anyone wants to see the PCA results, here is a distribution of the first PCA of demographic information (which captures about 25% of variation) in those who have (green) and haven’t (red) taken a genetic test. The difference is significant (p < 0.005), and is stronger than the association with any particular predictor, and than a logistic ensemble test of all predictors. The variance in the first PC is about 30% higher in those who have taken a test than those who haven’t, supporting that idea that those individuals who read our blog because of having taken a DTC test are drawn from a more varied demographic range.

One further interesting thing we extracted out of the data was a trend for those who felt more informed about genetics to be less likely to believe that parents should be able to consent their children to DTC genetic tests. Breaking this down on self-categorised level of knowledge, the percentage answering “No” to consenting children was:

Basic understanding of genetics: 16%

Could explain key concepts: 25%

Expert in genetics: 36%

Another one for further speculation, and definitely something to investigate in future surveys!

It’s funny, the antagonism for GMOs comes up several times in the free-text. Which is odd to me. Many of the same anti-GMO types are also eager to have unrestricted and unregulated companies work with their own sequence data.

Maybe Monsanto should get into personal genomics.

Thank you Daniel, Kate and Luke for taking a first cut at the survey data. It’s fascinating stuff and I’d like to strongly encourage our readers of a statistical mind to spend some time with it.

I also wanted to share a few of my own impressions (not backed by any fancy or colorful charts) on the topic of “public misconceptions,” as reported by Genomes Unzipped readers.

Education, Education, Education. As Daniel, Kate and Luke note above, the most popular misconception was some variation of genetic determinism and/or genetic exceptionalism. The two were often combined in comments lamenting a misunderstanding of the predictive power of genetics (genetic determinism) which, in turn, produces an outsized fear of genetic information (genetic exceptionalism).

Not surprisingly, the culprit most frequently fingered was poor education. What I found somewhat surprising, particularly within the Genomes Unzipped readership, was the number of respondents who shared a fairly bleak outlook on our ability to remedy this situation.

A typical response:

Given the rapid spread in the availability of genetic information, I’m not sure we have too many years left to fix this problem, let alone generations. Fortunately, not everybody is ready to throw up their hands. A more hopeful outlook was provided by a genetic counselor (an all-too-rare sighting), who wrote:

Although this reader (and several others) criticized some DTC genetic testing companies for over-hyping the utility of their products, several readers applauded commercial companies for the manner in which they have been able to successfully develop new educational tools and models.

Others Receiving Votes. For a handful of other topics, respondents were split with regard to the misconception/challenge. When it comes to the complexity of genetic information, some readers were concerned about the ability of consumers or patients to interpret and act upon that information without the assistance of a medical professional. Others were just as concerned by the “misconception” that the assistance of a medical professional is a perquisite – or even all that helpful – in understanding genetic information.

One of the milder responses in this vein expressed concern about “the attitude of some portions of the medical community and government regulators that somehow, we aren’t quite bright enough to take responsibility for our own DTC genetic tests.” Although not necessarily a misconception per se, numerous respondents used this question as an invitation to voice their opinion that they should be entitled to access their own genetic information without any intervention from medical professionals or the government.

Readers were similarly split on the value of governmental regulation. Some argued that many common misconceptions – in particular those pertaining to genetic determinism and the current value of genetic testing – could be addressed by cracking down on “charlatans” making unsupported claims about their products. Others argued that regulators were perpetuating common misconceptions, in part by “hold[ing] non-diagnostic genetic tests (i.e., those that convey relative risk) to a more stringent standard than other biological tests that convey relative risk.”

Thanks once again to all of our readers for sharing their thoughts. Remember, too, the second part of this particular question: “How do you think these misconceptions can/should be corrected?” We welcome your continued suggestions on how to address these misconceptions, through the Genomes Unzipped platform and elsewhere.

– Dan

there are large sex differences in the longevity movement too.

Ok, I was waiting to see if anyone else touched the psychology associated with “precisely zero female research geneticists who were willing to make their sequence data completely openly available” with a 10-foot-pole. But no one has. So I’m going to.

Yeah, that’s exactly what I need. To open myself up to criticism of my genome. Here’s a tip: I’m already not tall enough, not thin enough, and not blonde enough for our society. I’m sure I won’t be some allele-enough as well.

The 23andme survey asked about my bra size. I checked with a friend. There was no inquiry into his size—and you know what size I’m sayin’. Yeah.

I’m sure this means my risk-taking genes aren’t going to be up to snuff compared to the boys’ genes. It’s gonna be great to e-walk by the boy geneticists like a construction crew who hoot and snicker at my SNPs, CNVs, and my lack of a Y. Can’t wait.

And do you have any idea what the mommy boards are like? Egads. You can get trounced if you aren’t feeding your kids all-organic all-whole-foods artisan lunches. Can you imagine if they find out your kid inherited the diabetes allele from you? You’re gonna get crucified.

OK, partial snark aside: we are raised to be very cagey about our weight, our age, and many other aspects of our biology. Or at least I was. Maybe there’s an age component to the responses, and the hobbyists are younger? Also—-maybe they are safely insured, and not particularly worried about the insurance company finding out about their breast cancer alleles. Yet. I am.

I admit I wouldn’t share my sequence data completely only either (and I’m a female research geneticist), but perhaps for different reasons. I’m generally risk averse and am a bit worried about the unknown ways in which this data could be used. An informal poll of the various geneticists and scientists that sit around me (5 men, 4 women) also revealed zero people who would share their data completely openly. Not sure how much information only nine people can add, but there weren’t any obvious thematic differences between men and women that came out.

@Mary: Pish, boy scientists. I work with a bunch of them and while they’re very smart and very nice, they are also always in need of haircuts. How can we possibly take them too seriously? ;o)

@Joyce: the haircut gene will be found, probably. Ignored, but found. It’s not on this classic map of the Y from 1993.

But yeah–the insurance misuse issue is part of my concern (yes, I know there’s GINA, but it really hasn’t been tested with all the weasley ways insurers will try to get around it). I had a friend ask me if someday her landlord might look and see if she carries bipolar genes and not rent to her. I couldn’t tell her she was safe–that’s not covered in GINA.

I’m also very disturbed by the data-scraping that was done on the PatientsLikeMe site. (I don’t know if I can add another link without going into spam hell, but it was in a WSJ article called ‘Scrapers’ Dig Deep for Data on Web [Here is the link. -ed] ).

And although part of my post was just to be provocative and start the discussion, there are multiple reasons I would decline–some of which I would not disclose here either.

You can’t seriously believe that “restricting” and “regulating” our access to our own genetic data is something to be desired.

Certainly, if you want to keep your data private, you want to keep the government far, far away. They already tap our phones, scan our private parts, root through our tax receipts, and fingerprint us upon immigration. The last thing we need is for them to get a backdoor into our genome under the aegis of “restricting” and “regulating” it, for our own safety of course.

@John: so you trust for-profit companies instead?

A company run by individuals has to earn our trust, like Google or Illumina. The government has already irrevocably lost it.

@John: Well, I don’t share your full distrust of government. Nor your full faith in corporations. There’s some controversy about Google’s wifi sniffing, for example.

I sort of like legal checks on the power and responsibilities of corporations.